“Drop and Give Me 20!”

It’s 5:35 a.m. on a Monday morning and my alarm is chirping softly. It’s a kind alarm. Like a doting mother waking her sixth grader for school, it starts gently, then gradually gets more insistent (louder). I am no longer that sixth grader, so I don’t hit snooze. I don’t yank the cord from the wall or throw it across the room. I calmly turn it off and roll out of bed. I close the door behind me, slip on the dorky Kohl’s gym shorts and whatever t-shirt I’ve laid out in the next room. I head downstairs, flip on a light, peel and slice a banana, perhaps warm up some of yesterday’s coffee. Wordle is waiting, so I punch in a few letters while I nosh, perhaps scroll through the waiting headlines. Then, on with the sneakers and coat and out the door.

It’s a quick drive to the neighborhood fitness center. When I arrive around 6 a.m., my classmates are already helping our leader, Joanne, assemble the exercise stations for the day: a mat and medium weights here, risers there, exercise ball along the wall. In a few minutes, the peppy music will come on, an interval timer will buzz, and we will begin lifting, pushing, squatting, stretching, pulling and bending until the timer tells us move on to the next station. This will go on for 45 minutes.

Smile! You’re going to be sore tomorrow!

This is new to me. I have never been “an athlete.” I dabbled here and there—warming the basketball bench in grade school, jogging and playing a little intramural volleyball in college, road biking in my 30s and 40s, groaning and creaking through Iyengar yoga in my 50s.

In the past decade, I’ve been content with occasional bike rides and long walks. Or gym visits where an audio book and earpods make 30 minutes on an elliptical trainer go quickly.

What happened? Well….time happened, I suppose. Also, a steady diet of articles from the ever growing “health press.” Weed out the fad-ish and fanciful and you come up with a pretty secure consensus: get your heart rate up for 150 minutes per week and stress your muscles—all your muscles—twice a week.

That consensus was probably not too different when I was in my 30s, but lived experience is a powerful motivator. Back then, I wasn’t on a first-name basis with my chiropractor and my physical therapist. I had never seen a cardiologist. I didn’t wake with odd aches in strange places.

So I pant and sweat and and expand my familiarity with pop music hits that put some extra gusto into my Romanian dumbbell deadlifts. There are no guarantees, of course. But a couple of early mornings a week I get a little endorphin rush and a modest satisfaction that I’m keeping that guy with the robe and scythe at bay.

MSO Bachfest

The MSO’s Ken-David Masur.

Looking for Johann Sebastian? Not as easy as it should be. That venerated composer lands in a definite unsweet spot in the classical music timeline. Symphony orchestras usually work some Bach into their seasons, but today’s symphony orchestras (and orchestra halls) have roots in the 19th century and generally play music written after the late 1770s. There are ensembles that specialize in Bach’s baroque style (Chicago’s Music of the Baroque is one of the finest in the U.S.) and others who traffic in early music (before Bach) and contemporary music (waaayyy after Bach). But Bach buffs don’t always have it easy to get their fix.

Violinist Rachell Ellen Wong hit the A-Minor concerto out of the park.

Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra Music Director Ken-David Masur Is keeping Bach front and center in this city with strong German roots. Masur was born in Leipzig, where Bach lived for 21 of his most productive years. This season Mazur started an annual Bach celebration that overflowed from the symphony’s concert hall home into libraries, food courts, coffee shops and churches.

Unfortunately, I was out of town for most of the week-long festival, but caught the final concert Sunday afternoon: three baroque concertos and the show-stopping Magnificat, featuring seven vocal soloists, the MSO chorus and a large (by baroque standards) orchestra.

The Magnificat isn’t as popular as some of Bach’s other choral masterpieces—the B-Minor Mass and St. Matthew’s Passion—but it was a stirring showcase for the ensembles and singers, most of whom were drawn from the ranks of the chorus.

The highlight of the concert, however, was the Violin Concerto in A Minor, featuring soloist Rachell Ellen Wong. Baroque-style ensembles are small by modern symphony standards. And they are not a perfect fit for the orchestra concert halls of today. Two pieces featuring the accomplished harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani suffered because the keyboard was simply overwhelmed by the space. But Wong’s violin projected beautifully with clean baroque sound and a touch of vibrato just where it was needed.

There was another unexpected highlight after the concert ended. The reception hall of the Bradley Symphony Center was abuzz with activity, musicians from the orchestra and chorus mingled with audience members and singers from The Milwaukee Choristers, which performed before the main event. It was a community of Bach lovers—music lovers—celebrating the music and its making.

Rhapsody in Blue

In case you missed it, George Gershwin fans celebrated the 100th anniversary of his signature concert piece last month, which premiered in New York City as part of a program titled, “An Experiment in Modern Music.” It has become, of course, a staple of American orchestras. The MSO, in fact, performed it with resident artist Aaron Diehl in its opening concert in 2021.

Cultural historian Joseph Horowitz honored the occasion by digging in to the conflict and controversy surrounding Rhapsody in Blue in a recent post on ArtsJournal.com. Prompted by jazz pianist Ethan Iverson’s January New York Times column, which called it “The Worst Masterpiece,” Horowitz digs in to the conflicting reactions to Gershwin by classical composers from different sides of the Atlantic. While Europeans like Maurice Ravel and Arnold Schoenberg celebrated Gershwin’s attempt to fuse classical and jazz styles, Americans resisted the music and the concept. In fact, Horowitz points out that the piece was spurned by American orchestras until the late 20th century, considered to be marginal music appropriate to “pops” concerts. Moreover, he implies that this anti-popular stance was one of the the forces the pushed American classical music into its cerebral and esoteric style in the mid-20th century.

Read about it in Horowitz’s post or go deeper via his book, Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall. or via “The Gershwin Moment,” an hour-long documentary originally aired as part of NPR’s “1A.”

Richard Serra

Richard Serra.

His presence in the art world seemed almost as imperishable as the massive, steel-plate structures that were his life’s work. But Richard Serra died this week at the age of 85. I was able to see his 40-year retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2007, and “see” is probably the wrong way to describe the experience. As Serra explains in a segment from the series Art 21, he doesn’t sculpt COR-TEN steel as much as he sculpts space. You don’t look at his sculptures, you walk through them, around them, let them surround you. The Art 21 tours his major exhibit at the Guggenheim Bilbao and describes the complicated installation of his 60-foot tall piece, Charlie Brown, in San Francisco. Watch it here.

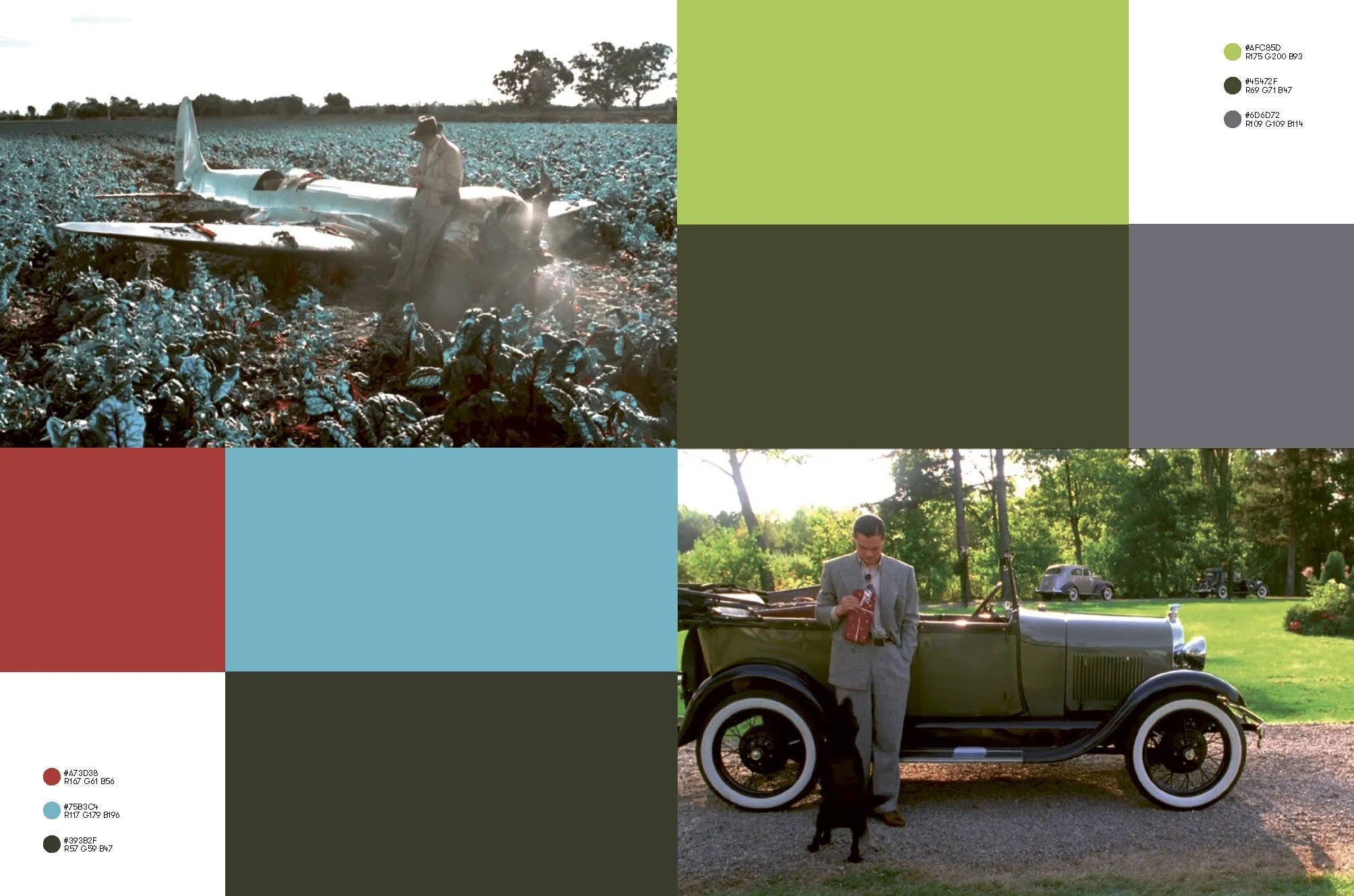

The Color of Film

Different color palettes in Martin Scorcese’s The Aviator. From Charles Bramesco’s Colors of Film: The Story of Cinema in 50 Palettes.

You’ve seen the fan magazines, the Hollywood histories, the gloriously illustrated coffee table books honoring the cinematic universes of Marvel, Harry Potter and Star Wars. But The Color of Film is quite different and quite beautiful. Charles Bramesco’s “Story of Cinema in 50 Palettes” presents movies from all corners of the cinema world (from Gene Kelly’s SInging in the Rain to Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers), but focuses on their basic visual vocabulary. Still images from the films are accompanied by a grid of three dominant colors from the image, identified by their hexadecimal and RRGGBB codes that are used by designers to pinpoint an exact shade.

With short essays on each film, Bramesco tells the story of cinema color in four historical-ish sections, ranging from Technicolor to 21st-century digital wizardry. His analysis is savvy, the visuals are beautiful. It will probably change the way you look at movies.

If you enjoy reading my musings, please share with a friend and subscribe. Have a good week.