Donuts!!!

Now that I have your attention…

Allow me to sing the praises of The Donut King, an unexpectedly moving and rich documentary that can be found floating about in the streaming ether. Yes, it is about donuts and parts of it will certainly make you crave a cruller. But the “king” of these donuts is Ted Ngoy, a Cambodian immigrant who made his fortune establishing independent shops throughout California. Director Alice Gu does let her camera linger on mouthwatering trays of elaborately decorated sinkers and dunkers. But Ngoy’s journey is more complicated and very American.

Ted Ngoy

Part of the wave of refugees arriving in California after the fall of Cambodia, Ngoy started a string of successful donut shops, and then went on to sponsor the visas of hundreds of refugees. He employed them at his shops, then started them off with their own franchise. While Dunkin’ Donuts was spreading shops across the East Coast and Midwest, Ngoy’s mom-and-pop shops were taking over the West Coast market. The Dunkin’ folks tried to break into the California market, but eventually, they just gave up.

There are harrowing descriptions of the rise of the Khmer Rouge in war-torn Cambodia, along with uplifting comments by Presidents Ford and Carter about the need for America to welcome immigrants. Ngoy and members of his family tell of the challenges of beginning life in a new country, and we then see them ascend into the suburban upper classes. And then . . . .

Well, that’s the rest of the story (as Paul Harvey used to say). Suffice to say that achieving The American Dream is not all sweetness and sprinkles.

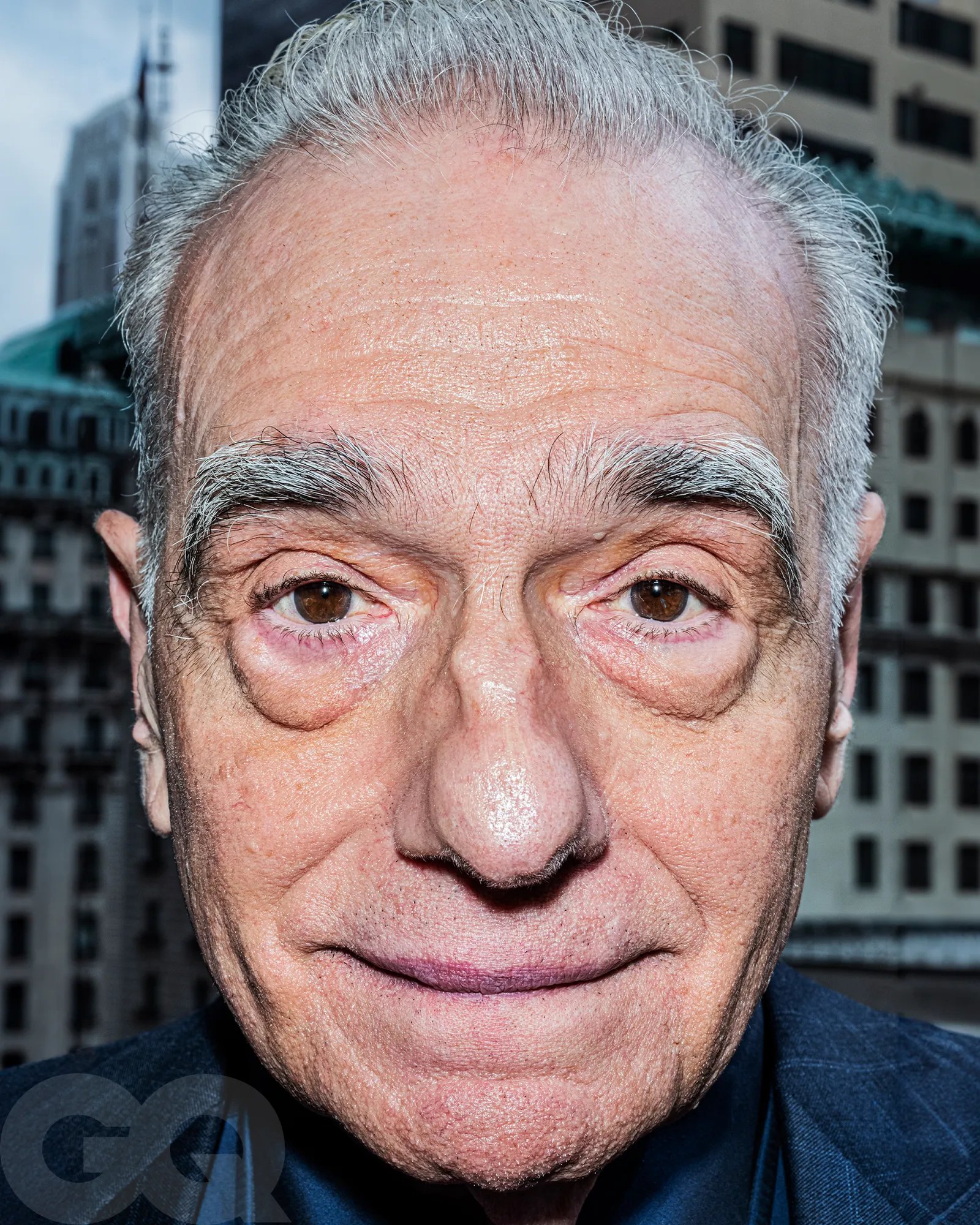

Marty Speaks

Photo by Bruce Gilden

Martin Scorsese turns 81 in November, and GQ magazine uses that milestone—along with the release of his latest film, The Killers of the Flower Moon—as an occasion to publish a substantial profile of one of America’s great living filmmakers. In a remarkable portrait written by Zach Baron, Scorsese reflects on his life: The loneliness of his asthmatic childhood and how it lingered into his later years. His affection for New York City and how it informs his directing, driving him to “Pack a startling amount of life into any given frame.” He talks about the movies he’s made, starting with 1967’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door, ones he really wanted to make and others that were pushed on him by the studios.

But telling his life story leads him to pose a powerful, existential question: How do I let go? In his life:

“Getting older is an exercise in letting go. Let go of anger . . . . Let go of fitting in. . . . Let go of other people’s opinions. . . . Let go of the idea that you might someday visit the Acropolis.”

And in his work:

“Let go of the idea that a movie needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. . . . Let go of the Academy’s opinion, of the idea of being part of Hollywood at all. . . . Let go of the experiments for the sake of experiments. . . . Let go of the studio system. . . . Let go of self-delusion, which is maybe the hardest thing of all to let go of. Shape the thing you’re making into a pure expression of the thing you’re making: “Cut away, strip away the unnecessary, and strip away what people expect.”

Photo by Bruce Gilden

In the final touching pages, looking over his collections of books, movie posters, awards, memories, Scorsese celebrates the getting and wonders just how he’s going to let go. Here’s how Baron introduces it:

Scorsese does try to be honest. If you ask him about impending mortality, for instance, which I did, hesitantly, he will tell you the truth. The truth, he said, is that “I think about that all the time.” I wish everyone could have been with us for what he said next. Because it was beautiful, and it’s hard to render beauty, but Scorsese spoke for about 40 minutes, after I asked this impertinent question about death, and I can only approximate it now, but here goes.

What follows is classic Scorsese: a free-wheeling, introspective, honest accounting of the drive that was behind his work and the challenge of thinking about its end. At 81, he is acutely aware of the idea of “spending time”: “Because it really means spending it,” Scorsese says. “It’s not going to come back.”

“And so there’s a balance between allowing yourself to exist . . . . and the other thing is a manic, manic desire to learn everything at once. Everything.”

Speaking of Marty…meet Sammy

Richard Widmark eyes his mark (Jean Peters, on the left) in Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street.

A brilliant historian of cinema, Scorcese is a champion of the B-movie director, Samuel Fuller. “If you don’t like the films of Samuel Fuller, then you just don’t like cinema,” he once said. (If you’re new to Fuller’s work, check out this documentary appreciation from the British Film Institute.)

Fuller’s Pickup on South Street recently showed up on my Turner Movie Classics feed and it’s as good an introduction as any. At the center of the story is a practiced pickpocket (Richard Widmark), who boosts a wallet that happens to contain a piece of microfilm headed from American communist sympathizers to the Kremlin.

Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street

The film is full of Fuller's trademark jittery and jargony dialog and bursts of raw violence. But to confirm Fuller's mastery as a director, you only need to watch the film's first three minutes, which takes place entirely in a crowded subway car. It's a symphony of mysterious glances. and shifting relationships. Bodies shuffle in and out as the train makes its stops, and we eventually see Widmark emerge from the crowd at the far end of the car. He sidles toward the camera, his glance eventually landing on a possible mark. But who are the other two guys--they glance at her, then at each other, then at the pocket-picking in progress. It sets up the who story of the film without a word of dialog.

Stay around for the great character turn by Thelma Ritter, an underworld insider on who totes around a suitcase of neckties, which she's selling to raise money to pay for her own cemetery plot. Just part of Fuller's morose and cool take on modern life. Cynical cinema for cynical times.

Roots

Lake Laura Hardwoods State Natural Area. October 5, 2023. @ 1:00 pm.

Living Tree

It’s said they planted trees by graves

to soak up spirits of the dead

through roots into the growing woods.

The favorite in the burial yards

I knew was common juniper.

One could do worse than pass into

such a species. I like to think

that when I’m gone the chemicals

and yes the spirit that was me

might be searched out by subtle roots

and raised with sap through capillaries

into an upright, fragrant trunk,

and aromatic twigs and bark,

through needles bright as hoarfrost to

the sunlight for a century

or more, in wood repelling rot

and standing tall with monuments

and statues there on the far hill,

erect as truth, a testimony,

in ground that’s dignified by loss,

around a melancholy tree

that’s pointing toward infinity.

Robert Morgan, 2012

Travels will take me away from my computer for a few days, so look for the next Friday Five in two weeks. See you then.