Golden Graham

Blurbs

It’s a rainy spring afternoon, perfect for a meander around your favorite bookstore. Footloose in the fiction aisle, you peruse and ponder, resolving to find a new author rather than continue your descent down the New York Times “Best Novels of the Past 200 Years” list. This one? No….neon orange dust jacket…trying too hard. What about this one? A little slim—small pages with big font. Too few words for $24.95. Ahh, here’s one. Stately reserved cover, not too thick, not too thin. Tempting. But of course, you don’t commit until you turn to the back cover to check out: The Blurbs.

If it is not a newly published book, you’ll find a list of concise but rapturous adjectives from published reviews. If it is brand-spanking new, the praise will be from familiar or not-so-familiar authors. These are “blurbs.” And folks in the publishing industry are talking about them.

Blurbs are not spontaneous outbursts from authors who just happened to have read the book in question. They are written by request, solicited by the authors. For years, publishers have, in fact, required authors to ask for blurbs like these. But in January, Sean Manning, the head of Simon & Schuster, decided that his company was ending this practice.

Authors have, not surprisingly, noticed. The New York Times has recently published not one, but two Op-Ed essays heaping hosannas on Manning and celebrating the blurbless writing life.

Christopher Buckley.

Rebecca Makkai’s “Too Busy Blurbing Books to Write One” is the more contemplative of the two. She was already on the no-blurb bandwagon before the S&S announcement, posting on social media that she was refusing blurb requests so she could spend time, you know, writing books (blurbing dozens of books a year, of course, requires reading said books). Despite this, she makes the case that “blurbs matter.” They enable curious readers to get a sense of the book’s style and substance via some well chosen words from pedigreed writers.

Christopher Buckley’s “The End of the Blurb. Thank God” offers a humbler, snarkier and more polysyllabic take (dad would be proud!). Using choice examples of what was once referred to as “log rolling” by the bible of snark, Spy Magazine, Buckley breathes a sigh of relief on behalf of authors everywhere, or at least those who write for S&S.

“After six books and almost two decades of mendicancy, my knees had to be surgically unbent. They weren’t the only damaged part of me. My self-esteem was so low, my self-loathing so high that I avoided mirrors.”

Golden Graham

Modern dance is about modern choreographers. The names say it all: The Paul Taylor Dance Company, Twyla Tharp Dance, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. Companies try to evolve after their artistic founders have gone—some flourish, others don’t.

Martha Graham’s “Errand into the Maze.” Photo by Malcolm Levinkind

Martha Graham has been gone for nearly 35 years, but her company, which is celebrating its 100th year anniversary next year, has endured. As the troupe’s Saturday night performance at Milwaukee’s Marcus Center demonstrated, it hasn’t done so by clinging to its history.

Graham’s stamp was certainly in evidence. The show opened with a Reader’s Digest version of her best known work, Appalachian Spring. Five dances from the full 50-minute ballet were introduced by Artistic Director, Janet Eilber, who read excerpts of letters Graham wrote to composer Aaron Copland. “Errand into the Maze” is another signature work, stark and pure in its high modern take on the Greek legend of Theseus battling the Minotaur. Here, the protagonist is a woman, the movement vocabulary is taut and dramatically charged.

Lloyd Knight in Jamar Roberts’s We the People.

While those two pieces proclaimed Graham’s legacy, two new pieces showcased a company eager to move forward. Hofesh Schechter’s Cave, created with the ballet star Daniil Simkin, is a high octane tribute to rave culture. It is indeed as described: “a visceral collective movement experience.” But watching a visceral experience isn’t as exciting as being part of one.

More exciting (and visceral) was We the People. Commissioned as a companion piece to Graham’s Rodeo, Jamar Roberts’s piece is a powerful evocation of American solidarity in trying times. Each of the four sections is preceded by a silent prelude (among them, Lloyd Knight’s solo, a wrenched conjuring of the history of violence against black men). After each preamble, bluesy, bluegrass-inflected instrumental music by Rhiannon Giddens brings forward the rest of the company, all clad in denim costumes by Karen Young. It’s a heady blend of defiance and celebration, replete with imaginative ensemble work and a dramatic sense of confrontation.

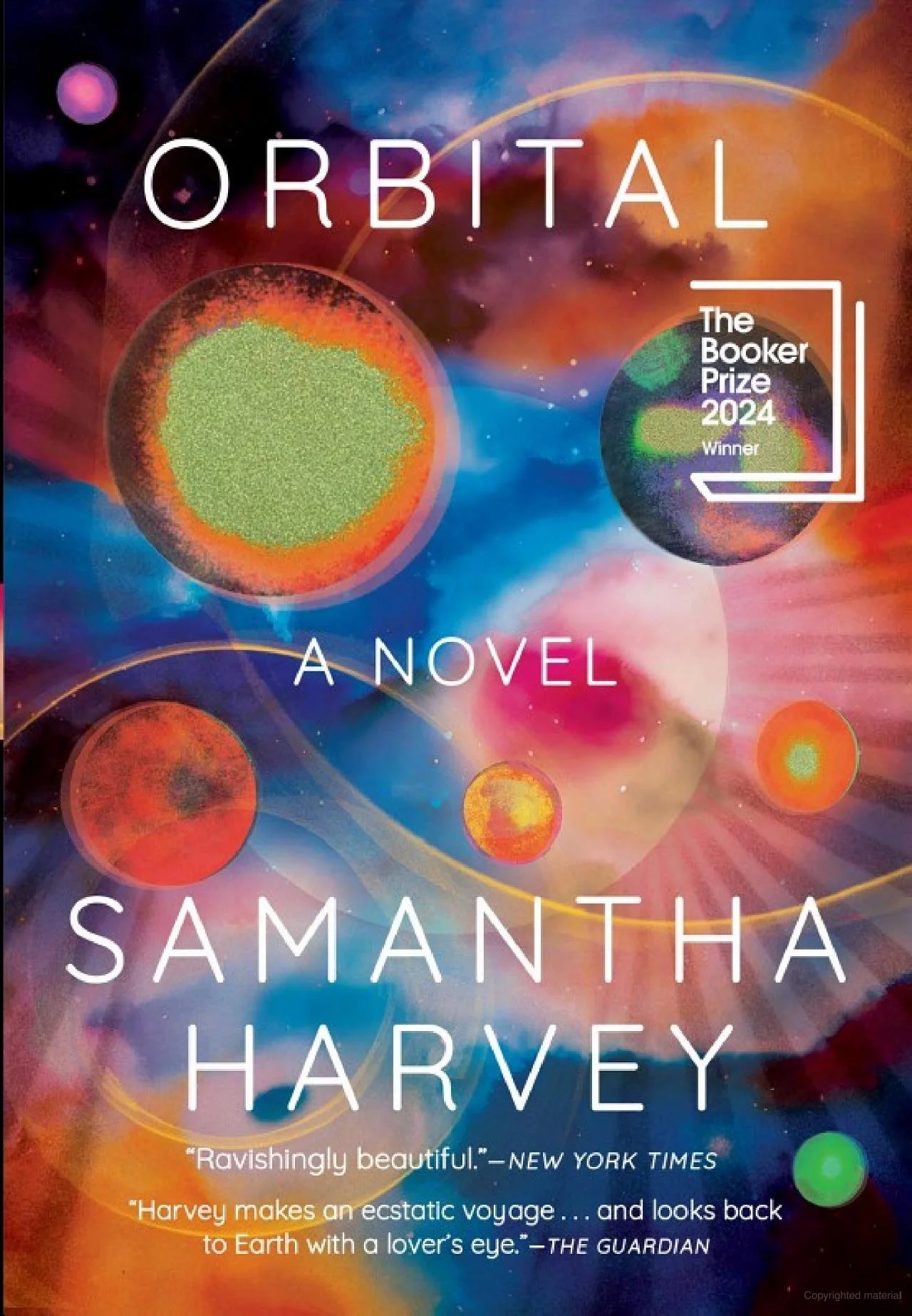

Orbital

We’ve all been in space. By proxy at least: Watching Neil hop down the LEM ladder. Swooping through the 2001 cosmos as planets and Tinkertoy spacecrafts waltz by. Floating in the void with spacesuited adventurers—real or CGI.

But—unless you’ve spent some time in orbit yourself— you’ve never experienced space like you do reading Samantha Harvey’s Booker Prize winning Orbital. Here you will find the discombobulations of life without gravity, where forks stay in place only with the help of velcro and muscles atrophy from the absence of gravity. Where the sun rises and sets sixteen times each “day.” Where cities disappear into the landscape in daytime, but come power-grid alive at night.

Harvey’s prose is by turns delicate and muscular, rich with the colors and textures of deserts, typhoons and oceanic expanses observed from far above. She probes the psyches of the six passengers on this orbiting space station, where “the small things are too mundane and the rest is too astounding and there seems to be nothing in between.” But Orbital is primarily (as one “blurb” put it) “a love letter Earth,” the world seen in fresh perspective, captured in beautiful prose. Here’s a sample:

“…two hundred and fifty miles beneath your feet the buffed orb of earth hangs too like an hallucination, something made by and of light, something you could pass through the centre of, and the only word that seems to apply to it is unearthly. It can’t possibly be real.”

Buster Keaton

We all could use a little comedy these days. Never fear, Buster is here. If you’re new to silent comedy, or doubt that it could hold it’s own in a 4K-Dolby Atmos world, the late Peter Bogdonovich wants to have a word. Or at least an hour and 47 minutes of highlights from Keaton’s career. The Great Buster: A Celebration, available to stream on several services, is a loving tribute to a comic genius, offering excerpts from early shorts to full-length masterpieces like Steamboat Bill, Jr., The General, and Sherlock, Jr. Escape and enjoy.

Roberta Flack RIP

Roberta Flack, who died last month at the age of 88, is best know for her whispery love songs—”Killing Me Softly,” “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”—but she knew the power of her understated style, as this recording from her debut album demonstrates. She recorded “Compared to What” a few months before Les McCann and Eddie Harris played it at the Montreux Jazz Festival. You probably know the song from their recording, but listen to the way Flack builds the catalog of social ills from sly smirking to full-throated rage.

Life has been a bit complicated lately, so I haven’t been able to keep The Friday Five on a weekly schedule. I’ll keep writing and posting when I can. Hope you keep reading. As always, thank you.